By Julie Young, Managing Director, Arizona State University Prep Academy, and VP of Student Education and Outreach at ASU

Originally published April 19, 2021 on digitallearningcollab.com

The wholesale jump to remote learning in 2020 will be remembered for many reasons, some positive and some painful. On the upside, our nation’s teachers, students, and families gained valuable skills and experience using 21st century technologies to support learning. On the downside, no one in distance education would have recommended the shocking pivot to this entirely different way of learning without design, training, transition planning, and preparation. It was truly a worst-case scenario, and what passed as “online or virtual learning,” left many with an understandably bitter taste.

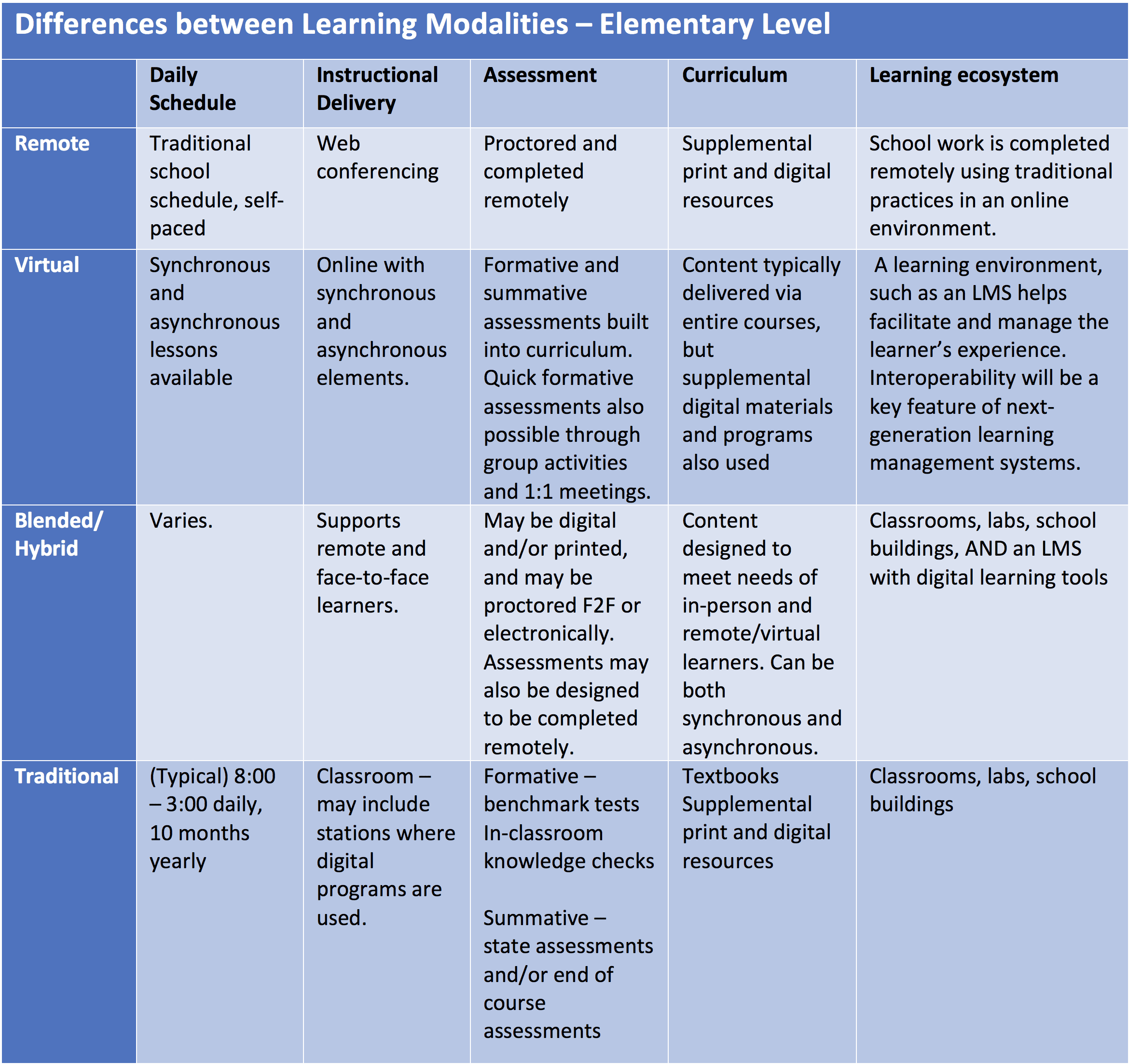

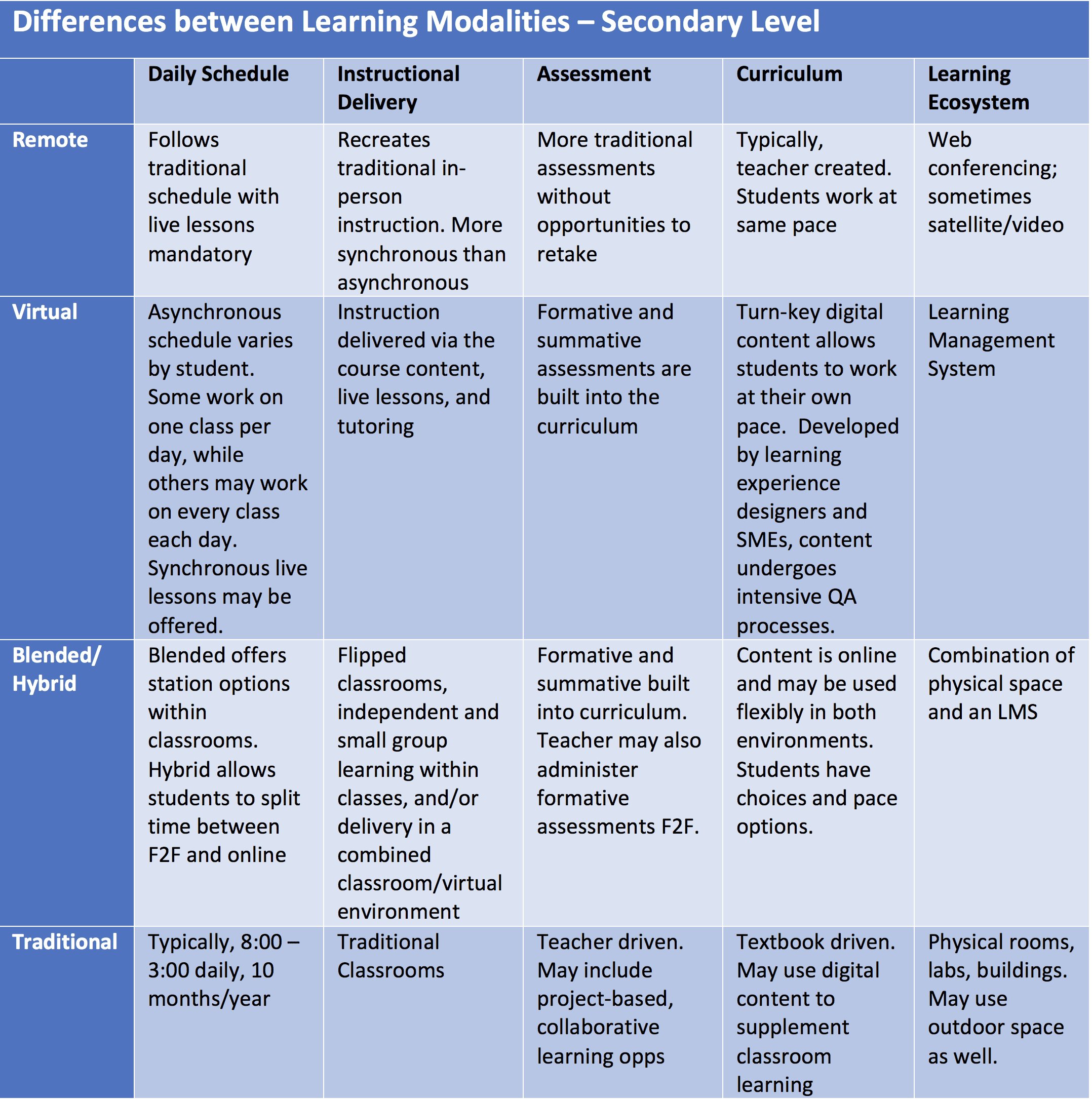

Even with the knowledge and skills gained relative to tech-based educational tools, there is still a serious lack of understanding about the differences between Web 2.0 tools and a well-designed virtual learning model. Perhaps it is time to put a finer point on defining remote, online, and virtual learning. I like to call these terms “the 3 cousins” because they are related but they are not the same. (Note that “digital learning” is often used as an umbrella term, with “digital” similar to “online” referring to the technology.)

Let’s start with remote learning. This is exactly what most of the world’s students experienced during the height of the pandemic. Remote learning simply transfers whatever happens in a classroom to a Zoom screen for learners outside of the physical classroom. For example, what was once a classroom lecture may now be nothing more than a talking head in a web conference. Many students experienced a “Brady Bunch” web conferencing screen for extended hours at a time, which is a poor simulation of a classroom. This may work in a short-term pinch, but remote learning is not what a long-term, well-designed virtual learning program should look like.

The term “online learning” simply refers to the vehicle or the educational medium for instruction to take place. In other words, the learning, regardless of where it takes place, is delivered via online tools and systems. Again, “online learning” is not the same as a well-designed virtual learning ecosystem, complete with thoughtful, research-based instructional practices, curriculum designed for online delivery, and student support mechanisms specific to the virtual learning environment.

Learning via a virtual versus face-to-face environment is obviously different. While the pandemic required educators to immediately use whatever tools they had at their disposal, for long-term virtual learning, it is reckless to simply transfer or replicate classroom learning to the online environment without employing thoughtful, design thinking. Quality virtual learning is designed learning, whether the end goal is a completely online, virtual, hybrid or blended model.

The differentiator for quality is in the learner experience. Learners in a quality virtual model should have much more agency. Time should become a variable, while learning remains the constant. The content and instructional design should invite and cultivate personalization, such as choices in pacing, scheduling and response choices. A well-designed program incorporates the power of adaptive content and assessments and offers varying learner pathways, depending on individual readiness and levels of mastery. Great design offers more flexibility for 1:1 or small group teaching and tutoring, and those sessions are far more richly informed by just-in-time, actionable data, readily available in a web-based environment.

To add to what educators have gained during this pandemic, I would suggest a few questions to consider. For example, how can the next virtual learning environment you create be designed so that what we see is less “teacher talking” and more “students doing,” in the form of peer collaboration, project-based learning, “away from computer” independent discovery, and family or community engagement? How can we staff to maximize student contact and support a “high touch” environment where students are always connected to life lines? How might a reduction in teachers’ time on writing lesson plans and grading be spent on individualizing learning? What are the best strategies for maximizing shorter synchronous times?

How do you incorporate counseling support, and what do things like homeroom, clubs, or extra-curricular activities look like in virtual programs? How can you strengthen relationships with students and families? Hint: none of this is about more social media. We often tell our teachers, “The phone is your friend.” Sometimes a simple phone call to a concerned parent or student can calm mountains of fears and anxiety!

Proven techniques and strategies already exist to address these questions and more, but this is where planning and training enter the picture. Virtual learning should incorporate ongoing coaching and training for teachers and program developers, particularly around design thinking. The details involved in crafting elements to support the learner experience in a virtual or hybrid delivery model are too seldom considered, partly due to lack of experience designing tech-supported learning models.

Still, now that educators have a taste of both the advantages and challenges of virtual learning environments, the need for support and training has increased. Incorporating the work of qualified instructional or “learning designers” will facilitate elevated levels of program design. But we will also need to cultivate and encourage a spirit of innovation if we are to realize high quality virtual learning models that equal or surpass the models we’ve known to this point—whether traditional or virtual. Let’s not settle for “going back to the way things were.” Let’s move forward to something better, using strong student support and thoughtful design as our building blocks.